The world needs a better spreadsheet

This is the transcript of my talk at NYC.rb on January 10th, 2017. It’s been edited for clarity.

Hey Hacker News, if you like this article, check out my podcast on work, Mercenary, or follow me on twitter.

I’m Matt Monihan, and am what you might call a consultant. I act as an interim CTO for non-tech companies, and develop applications when necessary, usually with Ruby on Rails. My company is called Voyager Scientific.

I typically deal with customers who want to digitize a paper process, and the most common use case is time-tracking. Things like, tracking hours of therapy delivered, the labor and materials on a construction site, etc.

Despite the cost of hardware falling, the speed of computation increasing, tools increasing in sophistication…for the businesses I work with, developing software is still prohibitively expensive.

This talk is meant to discuss some of the reasons this is the case, and provide some strategies to make software more affordable for those that need it most.

A few years ago, a close friend came to me and said, “Matt, I think I’m getting screwed.” I said, “What’s the problem?”

He said, “I’m working with a developer to create an electronic record of student information for our school. The guy I’ve hired to develop it won’t return my calls. I’ve paid him $10,000 so far, and he’s invoiced me for another $15,000. I can’t use what he’s delivered so far, and every time I question his work I get excuses. I feel like I’m being jerked around.”

I said, “Let me take a look at what he’s got.”

And, so I did, and it wasn’t great. But, it wasn’t that complex. I said, “I think I can build what you want in a weekend. I’ll tell you what, I’ll do it for $3,000 and you can cut your losses with this guy.”

And so I did. The application needed to store a student’s personal information, their parents’, and some health insurance records. I hadn’t built a rails application in years, but, despite that, I brushed the cobwebs off and got to work. It took about 4 hours to build, and 8 hours to deploy to rackspace. Long story short, I couldn’t use heroku. I still can’t believe it took that long to deploy.

The staff started using the system immediately. We fixed some minor bugs. In that state, it remained bug free for some months after it was deployed. It was just a simple CRUD system on a couple objects.

My friend was ecstatic that he didn’t lose a bunch of money and time. He’s happy.

I tell you this story because it’s common. And I expect that, to many of you, it’s probably unremarkable. If you’ve done freelance work, at some point or another you’ve probably been the savior, but you’ve probably also been the one with excuses. I’d like to tell you I’ve been the savior 100% of my career, but unfortunately, that hasn’t always been the case.

But, over the years I’ve developed a sense about the likelihood of a project being successful. Meaning, fulfilling the task it was meant to do, and being delivered on-time and under budget. Here are some of the things I’ve noticed.

The first is that we’ve reached an age where millennials are ascending to positions of authority within their organizations. Frankly, we’re getting older. And I say, “millennial“ to describe their expectations of what an acceptable user experience is. These people have long, positive relationships with consumer software, and are waking up to the reality that the UX of their workplace IT is let’s say, less than stellar.

When you’ve grown up with the responsiveness and ease of use of say, Facebook, Google, or Amazon, you come to expect it in all interfaces. The best example of this is the UX of working with an exceptionally long list. Let’s say a friend list with hundreds and sometimes, thousands of entries. In your application, do you use typeahead in the UI? Does the SQL query take a few seconds to return? When your budget is $3,000, how much have you allotted to mitigating this problem? Likely nothing, right?

Most software developers do not have the budget, or the expertise to cache like the pros.

As an aside, here’s a definition of what I mean by enterprise software in the context of my business.

What is an enterprise, and what is enterprise software?

Well first, what kind of enterprises am I talking about? For the purpose of this discussion, I’m defining enterprise software as software that is meant to serve a business purpose. The businesses I’m working with are typically 10 or more years old, and are funded with retained earnings, credit, or debt, not venture capital. 100%+ year over year growth over ten years is not the game these companies are playing. Though, they are interested in remaining competitive.

Furthermore, let’s assume this is for enterprises with less than 200 employees. Well beneath the Small Business Association’s threshold of 500. 200 employees at the median wage of $50k in the united states is $10 million per year.

It stands to reason that if you can afford to spend $10 million per year on people, spending $100k per year (just 1% of your HR budget) on technology to make them more productive is a no-brainer.

So, that’s the customer we’re working with.

Alright, so there’s higher expectations for software at work, that sounds pretty intuitive, what else?

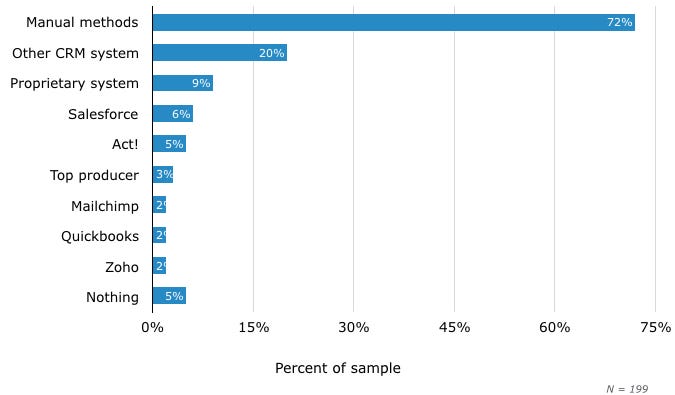

SoftwareAdvice.com polled thousands of organizations on their usage of CRM software(things like salesforce) and discovered that 72% use either paper or spreadsheets. An additional 5% used nothing at all. That’s compared to 20% who actually used CRM software. The rest used something else entirely.

Why?

I mentioned earlier that many of the use cases I work with are time-sheets. I.e. someone fills out a form each day, and that form is stored in a database. When building this, I need to keep a couple things in mind.

The UX of paper is still fantastic.

- It never runs out of battery.

- It can be both structured and schema-less.

- There’s no pesky validation errors to overcome.

- The resolution of an A4 piece of paper is a crisp 3508px x 2480px. For comparison, my MacBook Air is about a third of that at 1440px x 900px.

- and it never says, “oops something went wrong.” (Rails 500 error)

It’s also inexpensive. Both the paper itself, and the flexibility of the people hired to hold the pencil.

However,

- paper is tough to query.

- validations are worth having

- and, relational data is susceptible to error.

That’s where you’ll find thousands of people using and abusing spreadsheets. Ah, the spreadsheet, the killer one true killer app.

The biggest reason for paper + spreadsheets, however, is simply that they’re the only things known to most people.

So, I’ve mentioned higher user expectations, and the merits of people + paper as a substitute.

The last thing I noticed is the magical odyssey of requirements-gathering, and how it will make or break a project.

Requirements.

What are requirements anyway? Here’s a definition.

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Standard Glossary of Software Engineering Terminology defines a requirement as:

“A condition or capability that must be met or possessed by a system or system component to satisfy a contract, standard, specification, or other formally imposed document.”

OK. I feel like Michael Bolton reading the definition of money laundering in Office Space.

For our purposes, you might say they are what the software is required to do to complete a use case.

But, there’s more to them than that. Requirements have a relationship with time, and psychology.

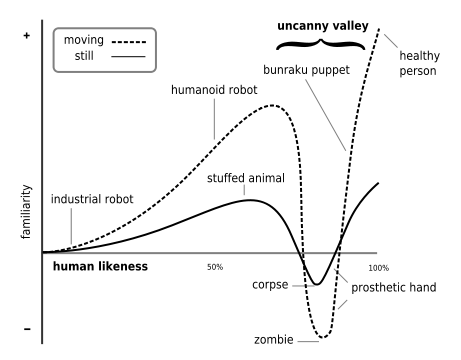

You might be familiar with the Uncanny valley in robotics.

The uncanny valley is a hypothesis in the field of human aesthetics which holds that when human features look and move almost, but not exactly, like natural human beings, it causes a response of revulsion among some human observers.

It’s a curve that as you build something that’s closer and closer to the real thing, just before you get to the real thing in human likeness, familiarity drops off a cliff into a valley. This is why corpses or zombies are scary.

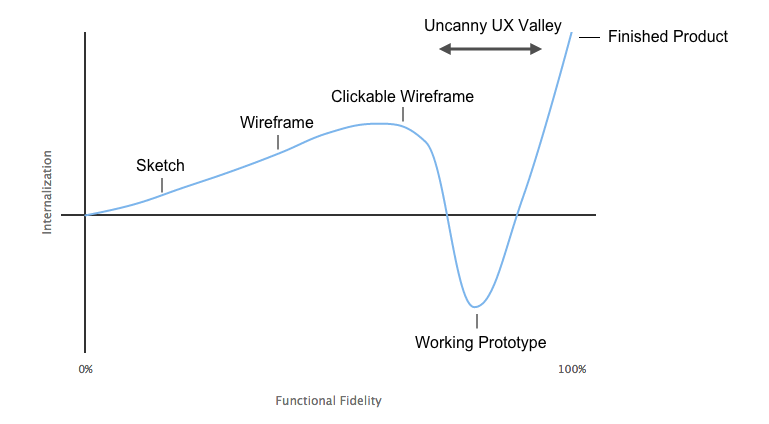

In UX, there’s an uncanny valley as well. At one end is your sketch based on a conversation, and on the other end is the platonic ideal of the completed application. But right at the bottom, here, is where your users finally internalize and start to intuitively understand how your application is going to impact their lives. This is also where you get the greatest quantity and highest quality feedback.

You start hearing things like,

- Can you just?

- How hard would it be?

- “I just remembered Jeff from accounting is going to need to sign off on this form, so he’ll need to have an email sent to him. And accounts payable, oh they need this and that…”

But, this is often too late. You’ll start getting feedback that call into question design decisions you’ve made much earlier in the process. Perhaps even call into question whether you should have built anything in the first place.

Oh, how things could have been different had we only known about this sooner.

That’s the question I pose to you, the audience. What are the ways we can stoke this conversation sooner?

The obvious solution is to call scope creep. You snooze, you lose, this wasn’t in the contract, or the sprint, backlog, or however you’ve laid out the project. So, we’ll fix it if we have more budget. This is the usually the most sane way to deal with this in the short term.

Another suggestion might be to be more rigorous in the progression of deliverables, spend more time, ask more questions, invest in better documentation. This, of course, means more budget. And, if you’re at the end of a project life cycle, it’s too late.

The goals of any good requirements-gathering process are perhaps the following:

Turning abstract processes and cultural norms into logical rules a computer can follow.

Documenting intent with code. I.e. Not only how something is used, but why it was built the way that it was.

How can we push our users into the uncanny UX valley sooner rather than later?

I think, broadly, the solution is to build prototypes that become the foundation of an application, without compromising our ability to extend and customize an application.

And most importantly, give that ability to non-developers.

What this means for me is that every application I build starts with a form builder and a spreadsheet. It has user authentication by default, and granular permissions for every object in the system(Read only, write mine, write all, etc). When an event takes place that requires a notification, there’s a UI to set that up.

If there is something I can’t do with the system, that’s when I get a developer involved.

So, what does this mean in practice? I should be able to design the schema of my application with a form-building UI, and produce a documentation that is both machine and human readable. That documentation should act as a single source of truth for the design of the UI, the business logic, and the database.

This, as an idea, isn’t really new, but I think it hasn’t been fully realized yet.

Salesforce is the biggest name in this game. It was born a CRM, but their platform can be used to build anything. You can build a sophisticated system as an administrator, but can pull in a developer when you need to do something more complex.

The only catch is that you have to sell you soul to Salesforce.

And that’s what this talk is really about, what is it our job to do? Is it to build applications, or to solve problems with technology? There’s a new category of job that’s emerging, and it’s one that straddles both the realms of user experience, and custom development.

When someone tries to hire me, the first thing I do is try to talk them out of it. Is the problem you say you have really a problem? Is it a problem that is best solved by technology?

If they make it past that conversation, I open up a google sheet and a google form builder, and try to create an MVP of the app right in front of them. And sometimes, that right there is enough.

Perhaps, In the end, the best piece of software is the one you never had to build in the first place.

Thank you.